A 17th-century ermita by the river, traditionally considered the border between Navarra and La Rioja (the official modern boundary is closer to Logroño, but nobody uses a paper factory as a landmark). A picnic area with shade trees and benches makes this a pleasant rest stop before the urban approach to Logroño.

The ermita is usually locked but the setting is the draw — riverside, shaded, and quiet.

You've left Navarra behind, and the Basque character that has been fading since Roncesvalles disappears almost entirely. La Rioja is Spain's second-smallest autonomous community and the smallest on the Camino Francés. The camino crosses it in about 60 km — roughly three days of walking.

The region is defined by wine. The Denominación de Origen Calificada Rioja is one of only two DOCa classifications in Spain, and the vineyards stretch in every direction from Logroño. Tempranillo is the dominant grape, and the range from young crianza to aged gran reserva provides excuse enough for extended tastings. The bodegas around Haro and Cenicero are open for visits, though they're off the camino route.

The landscape transitions from the green river valleys around Logroño to the drier, vine-covered hills heading west. The food is excellent — Rioja's pimientos, chorizo, patatas a la riojana, and lamb dishes are all worth seeking out, and even small-town bars take their cooking seriously.

To the south of Logroño lies Clavijo, where in 844 (according to legend) Santiago Matamoros made his first appearance. The story tells that during a battle between Ramiro I of Asturias and the Moors, Santiago appeared on a white horse to rally the Christian forces. The legend became the foundation myth of the Reconquista, and the image of Santiago on horseback with Moors underfoot appears in churches and cathedrals the length of the Camino.

For those with time, the Monasteries of Yuso and Suso in San Millán de la Cogolla (about 40 km south) are UNESCO World Heritage sites and among the finest monasteries in Spain. The Suso monastery is where the first written words in both Spanish and Basque were recorded.

Logroño is the capital of La Rioja and the first major city after Pamplona. You enter across the Puente de Piedra over the Río Ebro — a crossing that defined the city's fortunes for centuries.

The old quarter is compact and walkable. The Concatedral de Santa María de la Redonda (it shares cathedral status with Santo Domingo de la Calzada) has twin Baroque towers and houses a small painting attributed to Michelangelo — a Crucifixion, easy to miss in a side chapel. The Iglesia de San Bartolomé has the finest Romanesque doorway in the city. The Iglesia de Santiago el Real, the only one directly on the camino route, has an imposing equestrian Santiago Matamoros over the main entrance.

But the real attraction is Calle Laurel. This narrow pedestrianized street and its offshoots pack in upward of 50 tiny bars, each with its own signature pincho. The tradition is to go from bar to bar — one pincho and one glass of Rioja at each stop. Bar Soriano does one thing (grilled mushrooms with garlic oil and a prawn on top) and does it perfectly. The crawl typically starts around 8 PM and can go very late. If your albergue has a curfew, plan accordingly.

Multiple albergues operate in the old city. Hotels and pensiones cover all price ranges. Full services: hospital, pharmacies, outdoor gear shops, supermarkets, bus and train station. The Pilgrim Office near the cathedral stamps credenciales.

Logroño owes its existence to the stone bridge over the Ebro, which for a long time was the only suitable crossing point on this wide river. The toll extracted from pilgrims and merchants funded the town's growth. Its position on the Ebro and on the frontier between kingdoms made it one of the most fought-over cities in northern Spain — El Cid destroyed it in 1092, and it changed hands repeatedly between Navarra and Castile.

The 1521 siege of Logroño by French and Navarrese forces produced an unexpected legacy: a young Basque soldier named Iñigo López de Loyola was wounded defending the city. During his long recovery, he underwent a spiritual conversion that led him to found the Society of Jesus — the Jesuits. Ignatius of Loyola's story began here.

Logroño seems perpetually festive. The two major celebrations are San Bernabé (June 11), commemorating the 1521 siege, and San Mateo (September 21), the wine harvest festival — the bigger of the two and, predictably, focused on wine.

Leaving Logroño requires navigating the city — plenty of arrows, but many are painted low on curbs and hard to spot before dawn. From the cathedral, head straight along Calle del Marqués de San Nicolás, pass through two roundabouts, and turn left at the third. The route crosses the western suburbs before reaching open country toward Navarrete.

Accommodation in Logroño.

| Alaia Rooms Hostel 19€ 30 Booking.com |

|

| Albergue de Peregrinos Albas 16€ 26 Booking.com |

|

| Winederful Hostel & Café 21€ 18 Booking.com |

|

| Albergue Santiago Apóstol 12-20€ 76 Booking.com |

|

| Albergue Logroño 15€ 48 Booking.com |

|

| Albergue San Nicolás 22-25€ 28 Booking.com |

|

| Albergue Parroquial de Santiago Donativo€ 30 |

| Albergue de Peregrinos de Logroño 10€ 68 |

|

The Alto de la Grajera is less a mountain pass and more a gentle rise through parkland and reservoir on the western outskirts of Logroño. The Embalse de la Grajera was built in the 1880s for irrigation and has since become one of the few wetland areas in La Rioja — a pleasant green space with walking paths, picnic areas, and a bird observatory tucked into the scrub near the water's edge. Herons, coots, mallards, and marsh harriers are common.

The reservoir itself is strictly off-limits for swimming, but the surrounding parkland makes for an easy start to the day. There's a bar-restaurant near the park entrance if you need an early coffee.

Along this section you'll pass one of Spain's famous Osborne bull silhouettes — the black cutout billboards that have become an unofficial national symbol. Originally built as brandy advertisements in the 1950s, they were saved from a billboard ban by popular demand and are now protected cultural landmarks. You'll see more of them across Spain.

Look for the makeshift crosses that pilgrims have fashioned from bark and twigs and fixed to a fence near the high point of this stretch — one of those spontaneous Camino traditions that nobody planned but everybody contributes to.

The Osborne bull billboards date to 1956, when the Osborne sherry and brandy company of El Puerto de Santa María in Cádiz commissioned artist Manolo Prieto to design a roadside advertisement. The original bulls were 4 meters tall with the Osborne name in red lettering. As the herd grew, they were enlarged to 7 meters, then 14 meters. By the 1980s, some 500 bulls dotted Spain's highways.

When Spain banned roadside advertising in 1994, public outcry saved them. The bulls were stripped of their Osborne lettering, moved back from the road, and — after a Supreme Court ruling in 1997 — declared part of the cultural landscape. Around 90 remain today, including the one you see here above the highway near Logroño.

The reservoir has its own quieter history. The Marquis of San Nicolás, then mayor of Logroño, proposed the dam in 1877 to store irrigation water for the surrounding farmland. Construction finished around 1883. What began as agricultural infrastructure has become one of the region's most important wetland habitats.

From the park, the camino continues along a track that parallels the highway before branching into vineyard country. The walking is flat to gently rolling, with vineyards on both sides and the occasional farm road crossing. It's about 7 km from the reservoir to Navarrete, with no services along the way — the ruins of the Hospital de San Juan de Acre appear on your right as you approach the town.

Navarrete has been fought over so many times that very little of its medieval fabric survives. What remains is a compact hilltop town with a handful of covered arcades along the main street — soportales that hint at a more prosperous past. The town is built around a hill, as was common on this otherwise flat terrain, and the layout is straightforward: you walk in one end and out the other.

The pottery tradition here is the real distinction. Navarrete is the last surviving pottery center in La Rioja and one of the most important in northern Spain. Families like the Naharros and Torrados have been working the local clay for generations. At one point, 70% of the town's population was involved in ceramics. The signature piece is the Navarrete jug — wider than it is tall, with a glazed apron at the rim. If you have room in your pack and want a genuine Riojan souvenir, this is where to buy it.

The Iglesia de la Asunción, started in 1553 and finished a century later, has a Baroque retablo worth stepping inside for. The church keeps limited hours, but it's worth trying the door.

Climb to the Tedeón, where the castle once stood, for a picnic area and views over the surrounding vineyards and farmland. Several albergues and pensiones operate in town. Bars and restaurants line the main street, and a small supermarket covers provisions.

Navarrete's strategic hilltop position made it a target through the centuries. The castle, now gone, controlled the surrounding lowlands and changed hands between Navarra and Castile repeatedly.

The Hospital de San Juan de Acre was founded in 1185 to shelter pilgrims. It operated for centuries before falling into ruin. When the town cemetery was built in 1886, architect Luis Barrón salvaged the hospital's 13th-century Romanesque entrance and reassembled it as the cemetery gateway — you pass it on the way out of town. The portal has five slightly pointed archivolts with serrated decoration, and the capitals depict scenes of pilgrims eating, Saint George fighting the dragon, and — most famously — the legendary duel between Roland and the giant Ferragut.

Market day is Wednesday. The Virgen and San Roque are celebrated in mid-August. San Miguel, the patron saint, is honored on September 29 during the grape harvest — the streets fill with the smell of must and the sound of bands.

The N.A.C.E. national ceramics fair takes place periodically, celebrating Navarrete's pottery heritage with exhibitions, demonstrations, and sales centered on the traditional terra sigillata techniques.

On the approach from Logroño, you pass the ruins of the 12th-century Hospital de San Juan de Acre. Not much stands, but the footprint is visible. The original Romanesque entrance was salvaged and now serves as the gateway to the town cemetery — you'll see it as you leave.

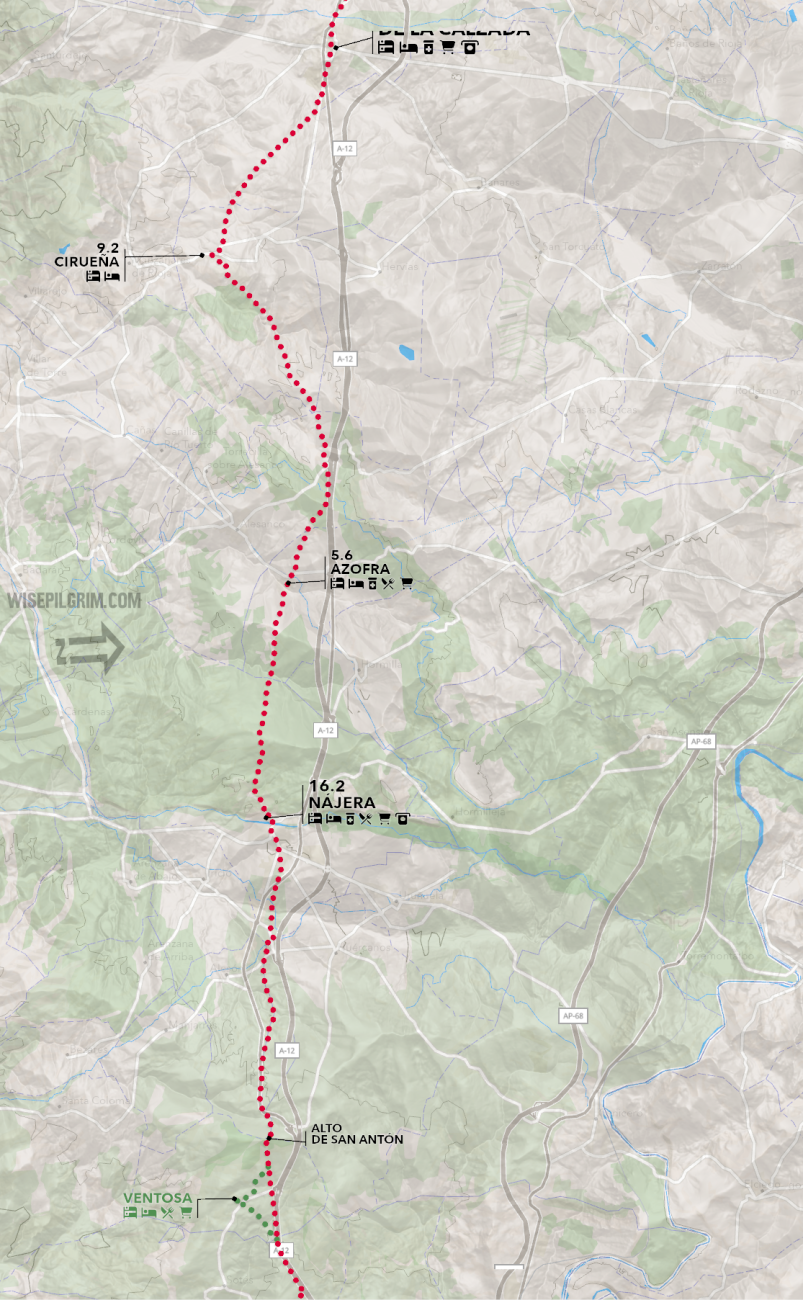

Leaving Navarrete, the camino passes through open farmland. The terrain is gently rolling, with vineyards giving way to cereal fields as you climb toward the Alto de San Antón. About 2 km past Navarrete, a fork offers two options: left to Ventosa (adding roughly 800 m), or straight ahead on the main route. Both rejoin before the pass.

Accommodation in Navarrete.

| Albergue de Peregrinos de Navarrete 10€ 48 |

|

| Albergue El Cántaro 15€ 28 |

|

| Albergue La Casa del Peregrino Ángel 10-12€ 18 |

|

| Albergue Pilgrim's 20€ 20 |

|

| Albergue Buen Camino 12€ 10 |

|

| Albergue A la Sombra del Laurel 15€ 30 Booking.com |

|

| Ikigai Albergue 15€ 35 Booking.com |

|

| Albergue La Iglesia 15€ 15 |

|

Ventosa has been sidelined by a rerouting of the camino that shaved 800 m off the distance but left the village off the main path. Despite this, most pilgrims still detour through — the two bars, an albergue, and a generally welcoming atmosphere make it worth the small extra distance.

The village sits on a small rise with views over the Riojan vineyards in every direction. The Iglesia de San Saturnino, a 16th-century church with a 17th-century brick tower, stands at the highest point. The main retablo inside, carved by Antonio de Zárraga, is dedicated to San Saturnino — the 3rd-century bishop of Toulouse who is one of the patron saints of the Camino.

This is a practical breakfast stop if you left Logroño or Navarrete early. Don't expect much beyond a bar meal and a place to sit — that's usually enough.

Ventosa first appears in records in 1020, when Sancho III granted the municipality to the Monasterio de San Millán de la Cogolla. The village has been tied to the Camino since at least the Charter of Logroño in 1095, which established this stretch of the route. Like many small Riojan villages, its fortunes have risen and fallen with the pilgrim traffic — and the recent rerouting hasn't helped.

From Ventosa, the path rejoins the main camino and continues to climb gently toward the Alto de San Antón. The terrain is open, with scrubland and vineyards. The pass itself, at around 640 m, offers the first views down into the valley of the Najerilla and the red cliffs behind Nájera. From the summit, it's a straightforward descent of about 8.5 km to Nájera through farmland and the occasional grove.

Accommodation in Ventosa.

| Albergue San Saturnino 14€ 40 Booking.com |

|

The Alto de San Antón (around 640 m) is a gentle pass between the Navarrete area and the descent into the Najerilla valley. The climb from either direction is easy — this is wine and cereal country, not mountain terrain.

Near the top, the ruins of a former monastery and pilgrim hospital dedicated to San Antón sit beside the path. Little remains beyond foundation walls and scattered stones, but the site gives a sense of how thoroughly the Camino was once served by religious institutions.

The views from here are the reward. To the west, the valley of the Najerilla opens up, with Nájera visible below and the red sandstone cliffs that back the town clearly outlined. On a clear day the Sierra de la Demanda rises beyond. No services at the pass — carry what you need.

The monastery of San Antón served pilgrims through the medieval period, offering shelter on this exposed stretch between the Navarrete area and Nájera. Like many Camino hospitals, it fell into disuse as pilgrim numbers declined after the Reformation and was eventually abandoned. The ruins are modest, but the location — at the highest point of the day's walk — made it a logical place to build.

The descent from the pass toward Nájera is steady and straightforward — about 8.5 km through open farmland, with the town gradually coming into focus below. The path is exposed with little shade. You enter Nájera through its eastern industrial suburbs, which are unremarkable, but the old town on the far side of the Río Najerilla rewards your patience.

The approach to Nájera through its eastern industrial suburbs is uninspiring, but persevere — the old town, pressed against red sandstone cliffs on the west bank of the Río Najerilla, has genuine character.

The Monasterio de Santa María la Real is the highlight and well worth the admission fee. Founded in the 11th century when King García Sánchez III reportedly found a statue of the Virgin in a cave in the cliffs — along with a lamp, a bell, and a bouquet of lilies — the monastery houses the Panteón Real, the royal burial place of the kings and queens of Navarra, León, and Castile. Over 30 carved tombs line the nave, and that of Doña Blanca de Navarra is considered one of the finest Romanesque funerary sculptures in Spain. The cave itself is accessible from inside the church. The Claustro de los Caballeros, built between 1517 and 1528, combines late Gothic vaulting with Plateresque tracery in the arches — one of the finest cloisters in La Rioja.

The caves in the red sandstone cliffs above the monastery are accessible and worth the short climb for views over the town and river. Some of these caves are over 3,000 years old, carved out during the Celtic period for defense. They've served various purposes since.

Several albergues, hotels, and restaurants operate in the old quarter. A supermarket and all services are available. The riverfront promenade along the Najerilla makes for a pleasant evening walk.

Nájera's name comes from the Arabic Naxara, meaning 'between cliffs' — an apt description once you see the red sandstone walls that hem in the old town. The city served as the capital of the Kingdom of Nájera-Pamplona from 923 to 1076, and it was during this period that it gave rise to the separate kingdoms of Navarra, Aragón, and Castile.

Sancho III el Mayor made Nájera his capital when Pamplona was under threat, and it was during his reign that the Camino was rerouted south from the mountain paths to its current course through the Riojan lowlands — a decision that shaped the Francés as we know it. He granted Nájera a charter, held the Cortes here, and established a market that helped fund the monastery.

The Monasterio de Santa María la Real was refounded in 1052 by García Sánchez III and handed to the Cluniac order by Alfonso VI. It survived Napoleonic occupation and the Mendizábal disentailment of the 1830s — barely — before being declared a national monument in 1889. Franciscans arrived at the end of the 19th century and have maintained it since.

The surrounding hills are also the legendary setting of the battle between Roland and the giant Ferragut, a story from the Codex Calixtinus. Ferragut, a Saracen giant, held the castle of Nájera until Roland discovered his only weakness — his navel — and killed him. The tale echoes David and Goliath and appears carved in capitals across the Camino, including at Navarrete's cemetery.

The fiesta calendar is busy. San Prudencio, patron of La Rioja, is celebrated on April 28. San Juan and San Pedro run from June 24 to 30. The biggest celebration is Santa María la Real and San Juan Mártir in mid-September — expect bullfights, music, and processions through the old quarter.

The Fiesta del Pimiento Riojano, celebrating the Riojan pepper, falls on the last Sunday of May. San Antón is marked on January 17.

Leaving Nájera, the camino crosses the Najerilla and climbs through open farmland toward Azofra, about 7 km away. The walking is easy and mostly flat. Along the way, notice the modern gravity-fed aqueducts that irrigate the surrounding fields — they're an interesting piece of hydraulic engineering, with sections that pass beneath the road rather than over it.

Accommodation in Nájera.

| Albergue de Najera 6€ 50 |

|

| Albergue de Peregrinos Sancho III - La Judería 13€ 15 |

|

| Albergue Puerta de Nájera 15-20€ 32 |

|

| Albergue Nido de Cigüeña 15€ 19 |

|

| Albergue Las Peñas 13€ 18 |

|

| Peregrino Najerino 14€ 22 |

|

| Pension San Lorenzo Booking.com |

|

Azofra is a quiet Riojan town that makes a practical breakfast stop if you set off from Nájera in the morning. The main street doubles as the Camino route — you walk straight through.

The municipal albergue is well-appointed, with double rooms rather than the usual open dormitories, and has a small plunge pool for hot afternoons. A parish albergue also operates. A couple of bars — Bar Sevilla and Bar Restaurante El Descanso del Peregrino — cover meals, and a small shop handles basics.

The Iglesia de Nuestra Señora de los Ángeles, built in the 17th and 18th centuries, sits at the top of the village with an embattled tower. Inside, a carving of Santiago Apóstol depicts him as a pilgrim rather than on horseback — the walking saint rather than the warrior.

On your way out of town, fill your water bottle at the Fuente de los Romeros, a medieval pilgrim fountain on the outskirts.

Azofra was founded during the Roman period and known as Ausebro. The name is Arabic in origin — roughly meaning the obligation of vassals to work the lord's land — a reminder of the centuries of Moorish influence in the region.

In 1168, Doña Isabel founded a pilgrim hospital here with a church dedicated to San Pedro and a cemetery for pilgrims who died on the way. The hospital operated until the 19th century, though no physical remains survive. The town's identity has always been shaped by the Camino — the main street follows the pilgrim route exactly.

The camino between Azofra and Santo Domingo de la Calzada passes through rolling farmland and the Rioja Alta Golf Club, where pilgrims share the bar with golfers — one of the Camino's odder juxtapositions. The route no longer goes through Cirueña but passes adjacent to it; a short detour left on the main road brings you to a coffee stop if needed. Ciriñuela has been separated from the camino by a residential development, but a bar is still accessible with a brief detour. About 15 km of easy, mostly flat walking to Santo Domingo.

Accommodation in Azofra.

| Albergue Municipal de Peregrinos de Azofra 16€ 100 |

|

| Pensión La Plaza 12 |

|

A tiny hamlet that has been separated from the camino by residential development. A bar is accessible with a short detour if you need refreshment, but most pilgrims pass without stopping.

The camino no longer passes through Cirueña but runs immediately adjacent. If you need a coffee or breakfast, turn left on the main road and walk about 200 m into the village. Otherwise, press on toward Santo Domingo de la Calzada.

Accommodation in Cirueña.

| Albergue Virgen de Guadalupe 15€ 15 |

|

| Albergue Victoria 15€ 10 |

|

| Casa Rural Victoria Booking.com |

|

Santo Domingo de la Calzada is one of the essential stops on the Francés — a town built by a saint specifically to help pilgrims, and still doing exactly that a thousand years later.

The Catedral de Santo Domingo is the centerpiece. Inside, a Gothic henhouse of polychrome stone — built in the mid-15th century — houses a live white rooster and hen, rotated every few weeks. They commemorate one of the Camino's most famous legends: a young German pilgrim named Hugonell was falsely accused of theft by an innkeeper's daughter whose advances he'd refused. He was sentenced to hang, and his body was left as a warning. When his parents returned from Santiago and found him alive on the gallows — sustained by the saint — they went to the authorities. The judge scoffed that the boy was no more alive than the roasted chickens on his dinner plate. At which point the chickens stood up and crowed. You'll hear the cathedral's birds before you see them.

Santo Domingo himself is buried in the crypt, fittingly beneath the road he built. The detached bell tower — the Torre Exenta — stands across the street, a Baroque structure nearly 70 m tall and the tallest tower in La Rioja. It was built separate from the cathedral between 1762 and 1765 because underground watercourses made the ground beside the cathedral too unstable. The tower is divided into two square sections and an octagonal bell chamber with four corner turrets, topped by a dome. It can be climbed for views.

The old quarter has arcaded streets and a pleasant plaza. The Parador de Bernardo de Fresneda, housed in a converted medieval hospital, is worth walking through even if you're not staying — the lobby preserves Gothic arches and original stonework. Several albergues, hotels, and restaurants operate in town. All services available.

The town is named after Domingo García, born in 1019 in Viloria de Rioja — a village you'll pass through later on the Camino. He tried to join the Benedictine order twice, at Valvanera and at San Millán de la Cogolla, and was rejected both times. He retreated to the forest near the Río Oja as a hermit.

From 1039 onward, with the support of Bishop Gregorio of Ostia, Domingo dedicated himself to improving the pilgrim road. He cleared forests, built a stone calzada (causeway) to replace the old Roman road between Nájera and Redecilla del Camino, constructed first a wooden and then a stone bridge over the Oja, and established a hospital and church. His engineering work effectively created a new, safer route through this section of the Camino. He is the patron saint of Spanish civil engineers.

Domingo died in 1109 and the settlement that grew around his hospital became a town, elevated to an episcopal see in the 1230s. His former pilgrim hospital operated until 1840.

The miracle of the rooster and hen — the Milagro del Gallo y la Gallina — dates to at least the 14th century. Variants of the same story appear in Toulouse and Barcelos, attributed alternatively to Santiago or to Santo Domingo. The live chickens have been maintained in the cathedral continuously for centuries, and part of the medieval gallows is displayed in the transept.

The feast of Santo Domingo runs from May 1 to 15, with the main celebrations kicking off on May 10. On that day, the Branches are blessed outside the cathedral, followed by the Procesión de la Rueda — a procession commemorating one of the saint's miracles, after which a wheel is hung from the cathedral vault. The days that follow involve considerable quantities of meat, all-night processions, music, and general revelry.

The Ferias de la Concepción, held in early December (roughly the 4th to the 8th), include a medieval market with around 90 stalls filling the streets around the cathedral and Plaza de España. Jesters, musicians, and merchants in period costume transform the old quarter.

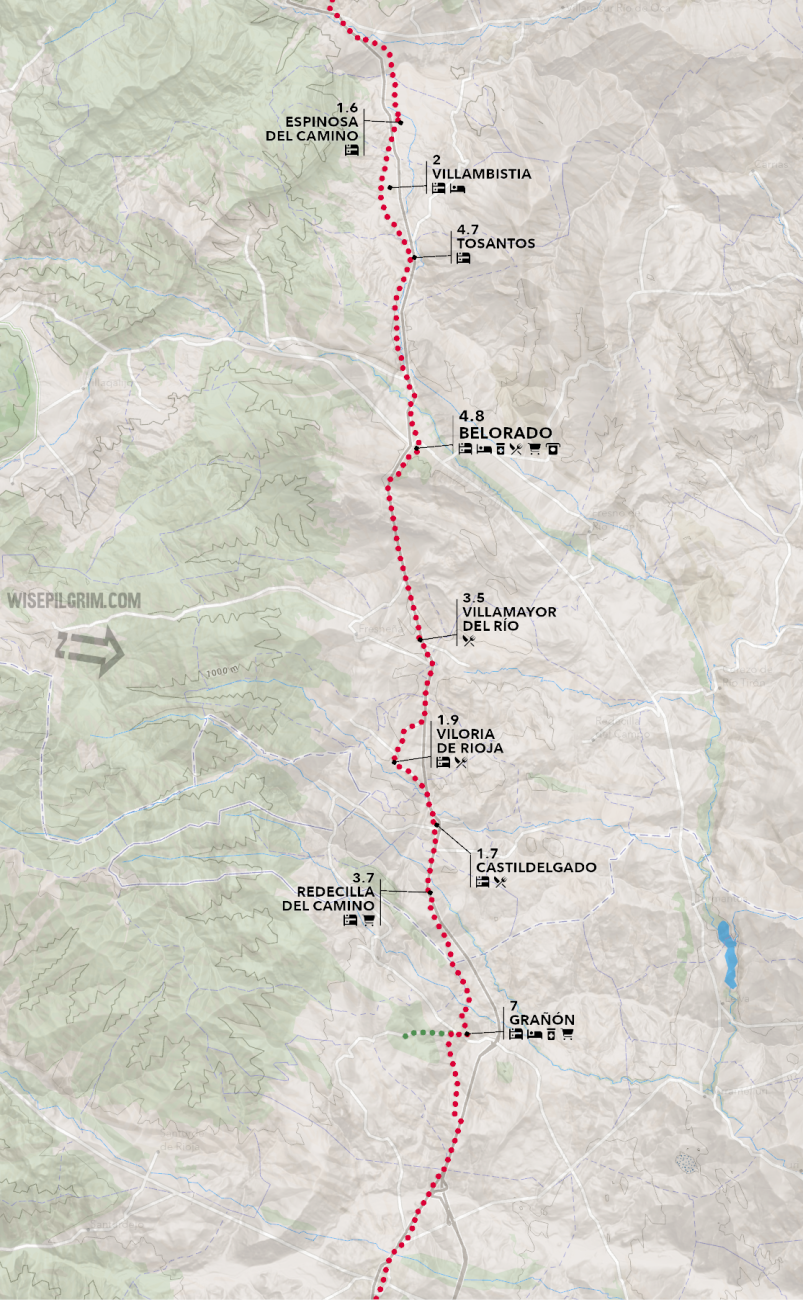

Leaving town, you cross the Río Oja on a rebuilt version of Domingo's original bridge. The river is often dry or reduced to a trickle. From here the camino continues through flat farmland toward Grañón, about 7 km away — the last village in La Rioja before crossing into Castilla y León.

Accommodation in Santo Domingo de la Calzada.

| Carpe Viam 22 Booking.com |

|

| Albergue Casa del Santo 13€ 169 |

|

| Hospedería Cisterciense ★★ |

|

Grañón is the last village in La Rioja on the Camino Francés, and it has earned a reputation far beyond its size. The parish albergue in the Iglesia de San Juan Bautista is one of the most distinctive experiences on the entire route. You sleep in the church itself — mattresses on the floor of the upper gallery, reached by a worn stone spiral staircase. Dinner and breakfast are communal and donation-based, prepared and cleaned up by everyone together. Prayer follows dinner. It's not for everyone, but those who stay here tend to remember it for years.

The church is worth visiting regardless. The 16th-century Baroque retablo is one of the best-preserved in the region, with rich gilding and detailed carving. Of the two monasteries that once served pilgrims in Grañón, only this altarpiece survives.

The village itself is small — fewer than 200 residents — with the solid stone architecture common to these Riojan border towns. A second albergue opened at Carrasquedo, about 1.5 km south in a forest setting, giving pilgrims a quieter option. A couple of bars, a small shop, and an ATM cover the basics. There's a pharmacy in town as well.

Beyond Grañón, the camino crosses into Castilla y León. You'll know — the landscape opens up and the architecture starts to shift.

Grañón's origins are military. The first written reference dates to 885, when "the castle of Grañón was destroyed" — though it was promptly rebuilt. The castle on Mirabel hill formed part of a defensive line against Muslim forces trying to push into Asturian-Leonese territory, alongside nearby fortifications at Pazuengos, Cellórigo, and Bilibio.

From 1044 onward, Santo Domingo began promoting pilgrim traffic along this stretch of the Camino, and Grañón grew accordingly. In 1187 Alfonso VIII granted the town a charter of rights, establishing the legal framework for the settlement that grew up around the pilgrim route.

The town's strategic position on the La Rioja-Castilla border meant it changed hands more than once during the medieval disputes between Navarra and Castilla.

The Fiesta de la Virgen de Carrasquedo falls on March 25, with Mass celebrated in the chapel and open-air dancing. On May 1, the Virgen de Carrasquedo is processed from the chapel to the Iglesia de San Juan Bautista, where she stays through the summer months. San Juan Bautista is celebrated on June 24.

The walk from Grañón to Redecilla del Camino is about 4 km of gentle terrain. Roughly halfway, you cross the regional border from La Rioja into Castilla y León — province of Burgos. There's no grand marker, but the landscape begins to change. The villages ahead are smaller, quieter, and more typically Castilian.

From Redecilla the camino continues through a string of small agricultural villages — Castildelgado, Viloria de Rioja, Villamayor del Río — before reaching Belorado, approximately 18 km from Grañón. Services are scarce between Grañón and Belorado, though most villages have at least a bar.

Accommodation in Grañón.

| Residencial El Cuartel Booking.com |

| La Casa de las Sonrisas 15€ 15 |

|

| Hospital de peregrinos San Juan Bautista Donativo€ 40 |

|